could be disassembled into a series of simple sine waves that when added together

would result in the original complex sound. The pitch at which we hear the complex

is called the fundamental since starting point or base to which the other sine waves are

added. The other sine waves are called overtones or harmonics. The collection of all the

various sine waves starting with the fundamental is called the harmonic or overtone series.

Overtones can ccur anywhere on the continuum of sound. They don't change the

pitch of the fundamental but add color and character which in some instances we perceive

as quality; in other instances as conveying information; but always as a means of

distinguishing and identifying the sound's source. The sound of the wind or the ocean

or a specific animal or Bob . . . or a cello, alto sax or glockenspeil.

When it comes to musical instruments the overtones no longer occur "just anywhere"

above the fundamental. They very specifically occur at 2x's, 3x's. 4x's, etc. the

pitch of the fundamental. We're not consciously aware that the overtones are integer

multiples of the fundamental, but we very definitely perceive the complex sound as

having the quality of purity.

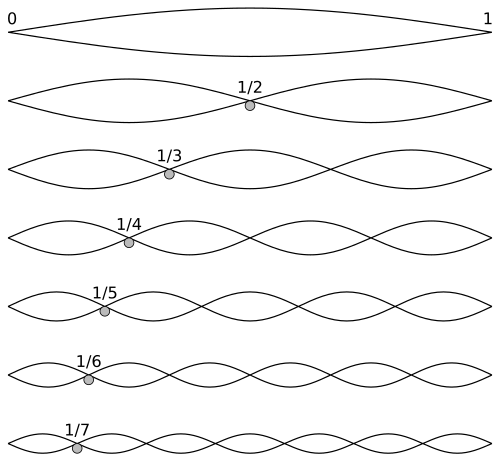

I grabbed this image of a vibrating string from Wikipedia's page

I grabbed this image of a vibrating string from Wikipedia's page

"Harmonic Series (music)" thinking it's public domain. If it's not,

please let me know and I'll make an effort to replace it with a

similar image that is.

In any event, what you can see in the image is that there are two crests, then

three,four,five,.. crests of each overtone for the one crest of the fundamental.

Each overtone is vibrating 2,3,4,5 times as fast as the fundamental, but their

cycles all align with the start and end point of a single cycle of the fundamental.

This alignment gives an easy explanation of why we consider tones whose overtones

are only integer multiples of the fundamental as being pure, but I don't know if that's

actually true. Since the overtones of musical instruments have been found to adhere

to this particular ordering of the overtones however, there's no debating this simple

fact of nature and no end to wondering why pure tones elicit a strong enough guttural

in humans to warrant their spending time crafting and playing flutes as early as 50,000 BC!

So far, we're only talking about the quality of an individual tone at a particular frequency

that does not move from that frequency over time. But we don't generally listen to a single

unchanging tone for extended periods of time. Nor do we listen to tones sliding around willy-nilly.

What we listen to are melodies. Tones that move by discrete amounts. And melodies don't just

wander all over the place. They resolve to a satisfying and logical place of rest. It's not a

logic to grasp with our capacity for reason, but a visceral logic. Growing out of our perception

of overtones that are integer multiples of the fundamental producing the purest individual tones,

neighboring tones that are separated by ratios corresponding to the integers separating the

overtones are perceived as the ideal spacing between them.